| CATEGORII DOCUMENTE |

| Animale | Arta cultura | Divertisment | Film | Jurnalism | Muzica |

| Pescuit | Pictura | Versuri |

British typical sports

INTRODUCTION

Sport is the most popular thing in the world. We don't realize it but all of us have something to do with sport, we run, we sit down, get up we do all kinds of sports movements, and this happens because we have a dynamic lifestyle, we have to move very much.

Sport is very important for us, for

our health as we always want to progress, to attain some kind of performance.

Practicing a sport we will have a healthy body and a strong mind, as the Latin

proverb says: "Mens

I've chosen this project: "Typical

English sports" because I want to present some interesting facts about typical

sports. The typical British sports are FOOTBALL, CRICKET, TENNIS, SNOOKER and

HORSE RACING. As we all know some of the most famous sports in the world such

as football, tennis and cricket ware invented in the

The first sport I dealt with in my

paper is tennis. Tennis is one of the most exhausting sport but in the same

time is one of the most popular. Everyone has heard of the grand slams of

The second sport that I'll present is

football. There are some historical data which confirm that football was

practiced in many ways a long time ago. The first ware the Romans, then the

Greeks and it was known even in the Far East China. It was practiced in many

different ways and it was different of nowadays football. Football as we know

it today was born in

Last, but not least sport is cricket.

It is a beautiful sport, it has a lot of rules it is quite difficult and is not

as popular as football. The nr.1 sport in

In conclusion, sports should and must be one of the major activities in one's life as it helps us to stay healthy and fit and always have a clear mind.

CHAPTER I

TENNIS

I.1

The Lawn Tennis Championships at

The Championships start six weeks before the first Monday in August and last approximately a fortnight, until all events are complete.

There

was a temporary three-plank stand offering seats to 30 people, the total

attendance for the final was 200, and the weather was grim. Welcome to

In common with the other 21 hopefuls competing for the first prize valued at 12 guineas, plus a silver challenge cup valued at 25 guineas, Gore was not a devotee of the new sport of lawn tennis. A keen follower of cricket, Gore also played real tennis and rackets. The day of the tennis specialist was still far away.

In fact in 1877 tennis was very much an afterthought at the All England Club, which had been founded nine years earlier to promote the game of croquet. But as the new game of tennis began to overtake the more sedate croquet in the minds of a growing middle class population, it was decided to incorporate tennis courts into the club facilities.

There were, of course, strict regulations in the matter of attire. A notice on the clubhouse door advised 'Gentlemen are kindly requested not to play in shirtsleeves when ladies are present.' The greater physical exertions of tennis also required more than the post-croquet rinsing of hands and the enterprising Dr. Henry Jones, a committee member and general practitioner, built at his own expense a bathroom, for the use of which he charged a fee.

The weekly sporting magazine The Field, in whose London offices the All England Croquet Club had been founded in July 1868, became one of the sporting world's earliest sponsors when it publicised 'a lawn tennis meeting, open to all amateurs, entrance fee £1 1s 0d' and put up the trophy. A footnote indicated that rackets and 'shoes without heels' should be provided by the players themselves, though balls would be supplied by the club gardener.

Dr.

Jones, who was appointed referee, did much more than introduce bathroom

facilities to

The

scene of the first

Though the tournament's opening day, Monday July 9, had been set, the event was the victim of weird scheduling. After the semi-finals on Thursday July 12 the competition was suspended to leave the London sporting scene free for the top occasion, the Eton versus Harrow cricket match at Lord's, over the next two days, with Wimbledon's first final due to be played the following Monday, July 16.

Nobody bothered to record the crowd numbers for the historic first day's play, when one of the entrants, C.F. Buller, failed to turn up, reducing the number of matches from eleven to ten. The eleven survivors were whittled down to six the following day and then to three. Since the concept of using byes only in the first round was still some years away, William Marshall received a free passage into the final while Gore beat C.G. Heathcote, an All England Club committee man.

After the weekend's excitements of the cricket at Lord's, the day of Wimbledon's final, for the first time but certainly not the last, turned out wet and was postponed - not to the next day but, in accordance with those more leisurely times, until the following Thursday.

The paid attendance of 200 for the final (at a shilling a head) again had to put up with damp and dreary weather as Gore claimed his niche in sporting history by outclassing Marshall 6-1, 6-2, 6-4. The one-sided match, delayed an hour by rain, lasted only 48 minutes.

There is no greater test in tennis than the switch from clay to grass courts in June.

For

the top players, the grass season lasts no more than four weeks and as it

immediately follows the French Open, most players who lose in the early rounds

at Roland Garros will head to

Players must contend with low skidding balls and irregular bounces

They have a very short time to adapt from the high bounce of the slow clay court to the unpredictability of the grass where the average rally in a men's match is four strokes.

In addition the playing characteristics of the game can change on a daily basis depending on the weather, the amount of play the court has had and the length of the grass.

The bounce is generally fast and low so the ability to shorten backswings, serve and volley well and use slice will all contribute to grass court success.

Playing on grass demands that you come up with effective solutions to the following challenges:

The ball bounces low and often skids

The court is often slippery

There are often bad bounces

Top players make it a target to finish the points off quickly and allow the ball to bounce as little as possible on their side of the net.

Younger players should also follow this tactic.

It's important to move in after the serve or the short/mid-court ball and win the point with a volley or overhead.

The slipperiness demands using a lot of small adjustment steps to get in to the correct position. You will probably need to lower your centre of gravity to get down to the low or bad bounce.

It's worth investing in a pair of grass court shoes -the ones with the little pimples on the soles. These will really help you to get a better grip on what can be a slippery surface.That means bending your knees!

Quick adjustments in the swing pattern and footwork are constantly needed so any movement or co-ordination weaknesses will show up immediately.

And as points tend to be short, it is important to keep good focus. Any lapse of concentration can lead to a service break.

On grass the serve and return plays a huge part in determining the outcome of the point, so it is very important to use your serve effectively.

At the beginning of the grass season, the grass tends to be a bit longer and the courts can be quite soft as they have not been often used and there has not been enough sunshine to harden them up.

If this is the case, try to use the slice serve to keep the ball low.

Henman has had his best success on grass

Later in the season, if the court is hard and the grass is shorter, the flat serve will work better as the courts will be faster.

Top spin second serves will be more effective too as the ball will bounce higher.

Don't forget the body serve, especially if the court is uneven. A slice body serve on grass can be almost impossible to return.

You may also find the following tactics useful:

Serve wide with a bit of slice and attack to the open court. The grass and the slice will keep the ball low, taking your opponent out of position and making it very tough to hurt you with the return.

Attack up the lines. Try to take control of the point by hitting hard, flat and deep up the line off short and mid-court balls.

The ball travels very fast off the grass when hit flat, forcing your opponent to defend. Be prepared to follow that shot in so you can put the ball away with a volley or overhead.

Use the drop shot, short slice and stop/drop volleys on grass. If you use these shots effectively, they should land in the areas of the court which are soft and therefore will hardly bounce!

Players tend not to play in the front half of the service box so this area of the court does not harden up in the same way as the rest of the court.

I.2 All the basics of scoring

There's no getting away from it, tennis has an unusual scoring system.

The score does not go up in units of one or even in units of the same amount.

The first point in a game is called 15 and the next 30. So you'd think that the next point should be 45 - but it isn't, it's 40.

And the score of a player who has not won any points is not 'nil' or 'zero', but 'love'.

This is said to come from the French word 'oeuf', which means 'egg' and is shaped like a zero. The server's score is always called first by the umpire.

So if Player A is serving to Player B and Player B wins the point, the score is love-15.

If Player A wins the next point the score is 15-all, and so on.

I.3 Scoring basics: games

The first player to win four points wins a game.

So if a player wins four points straight their scoring will go 15-0, 30-0, 40-0 then game.

The exception is if both players win three points each (i.e. 40-40) which is called deuce.

Then the winner is the first player to then win two points in a row.

I.4 Tennis equipment guide

Tennis has always been something of a fashion show.

It began in the 1930s when Frenchman Rene Lacoste promoted his own brand of sports shirts by sporting the Lacoste crocodile logo on court.

Now, tennis fashion is now a multi-million pound industry.

But specialist equipment does not have to be expensive. All you need is a racquet, balls and trainers.

You could spend anything up to £800 on a full outfit and racquet. But you can pick up kit including a racquet for as little as £50.

But the racquet may be the one piece of equipment worth spending a little more money on.

CHAPTER II

IMPORTANT PLAYERS WHO PERFORMED ON

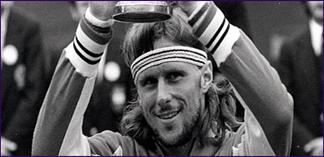

II.1 Bjorn Borg

![]()

Though his modern-era record

of five Wimbledon Singles Championships has been overtaken by Pete Sampras,

Bjorn Borg remains at the pinnacle of the all-time greats of The Championships

by virtue of two statistics: those five successive victories between 1976 and

1980 and the fact that he also pulled off in three consecutive years the most

difficult "double" in tennis, victory on clay at the French Open and on grass

at Wimbledon.

Though his modern-era record

of five Wimbledon Singles Championships has been overtaken by Pete Sampras,

Bjorn Borg remains at the pinnacle of the all-time greats of The Championships

by virtue of two statistics: those five successive victories between 1976 and

1980 and the fact that he also pulled off in three consecutive years the most

difficult "double" in tennis, victory on clay at the French Open and on grass

at Wimbledon.

Becoming

champion in quick succession on such alien surfaces has been achieved before,

most notably by Rod Laver in his Grand Slam years of 1962 and 1969, but since

Borg only Andre Agassi has managed to win both Roland Garros and

There

was, alas, a price to be paid for Borg's genius, and it was a heavy one. After

annexing 11 Grand Slam singles (six French, five

In an astonishing sequence Borg demolished seven opponents, culminating with Ilie Nastase, without dropping a set. It was only the fourth time a man had done that at Wimbledon, and it has not been accomplished since.It had thus been demonstrated in devastating fashion that Borg's finest qualities, speed about the court, heavily topspun groundstrokes and mental strength, translated readily from clay to grass. It was that mental strength, allied to his sheer never-say-die quality, which subsequently rescued him four times from looming defeat in his incredible run of Wimbledon success.In 1977 he trailed Mark Edmondson by two sets in the second round before sweeping the next three, and in the semi-final his close friend Vitas Gerulaitis was a break up in the fifth set before succumbing to lack of belief, since he had never beaten Borg.In 1978 he trailed on the opening day by two sets to one against Victor Amaya before finding his rhythm, having newly arrived in London from triumph in Paris. Two years later Vijay Amritraj led Borg two sets to one in the second round, and Borg was taken to a fourth set tie-break before prevailing. Beneath that headband worn severely low on the forehead, the will to win was strong as ever.

It

was needed in the 1980 final against McEnroe, a match nominated by many as

BJORN BORG'S VICTORIES:

Champion:1976,1977,1978,1979,1980

Runner-up: 1981

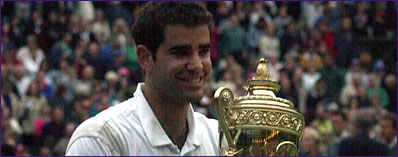

II.2 Pete Sampras

![]()

With seven Wimbledon

Championships - 14 Grand Slam titles in all - Pete Sampras has the most

outstanding record of any of the men's Champions. Although the records and statistics

are the dry proof that Sampras was king in his time at the All England Club,

sport is not just about numbers. What grips us, the lucky few who get to sit at

the court side, is the passion, the fear, the blood, sweat and tears that

separates the players from the champions and the champions from the truly

great.

With seven Wimbledon

Championships - 14 Grand Slam titles in all - Pete Sampras has the most

outstanding record of any of the men's Champions. Although the records and statistics

are the dry proof that Sampras was king in his time at the All England Club,

sport is not just about numbers. What grips us, the lucky few who get to sit at

the court side, is the passion, the fear, the blood, sweat and tears that

separates the players from the champions and the champions from the truly

great.

Passion? Sampras? Oh, my, yes. Sampras was never the most expressive or effusive of characters on court, but there was a fire in him that burned brightly and scorched all who came near it. His whole life was devoted to achieving greatness and then hanging on to it. For six years between 1993 and 1998 his every waking moment was consumed with the thought of winning and maintaining his position as world No. 1. He did it, too.

During

that spell, he won five of his

Every

year he would come to

Then

there were the occasions when Pete was in his pomp. The 1999 final against

Andre Agassi was possibly the greatest display of grass court tennis that

Round by round he gathered momentum until he was ready for Agassi. His fellow American had just won the French Open, he was the story of the moment having hauled himself back from a ranking of 141 and reinvented himself as a champion. Agassi was at his peak. And in the first set he had the temerity to manufacture three break points on the Sampras serve.

That was it. That was the moment Sampras moved from champion to genius. He snatched back the break points and then took off. For a couple of minutes Agassi shook his head and tried to work out what had happened but by then the first set was gone and he was a break down in the second. It was not that Agassi was playing badly, it was just that Sampras was sublime.

'Today he walked on water,' Agassi said later. Sampras said simply: 'Sometimes I surprise myself.' He ended the match on a second service ace - naturally.

He

was back the next year for his last Championship victory at

PETE SAMPRAS

Singles Champion:

CHAPTER III

FOOTBALL

III.1 Some of the basic rules behind the beautiful game:

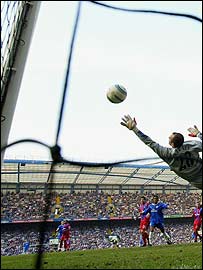

![]()

All defenders will tell you stopping goals is

the most important thing in football. Talk to a striker and you'll be

reminded they're the ones with the most important job! A team obviously needs

both. But the simple truth is that you can't win a game without hittting the

back of the net with the ball. Here are some of the basic rules. All players

must be in their own half at the kick-off and the first touch of the ball must

go forward.

All defenders will tell you stopping goals is

the most important thing in football. Talk to a striker and you'll be

reminded they're the ones with the most important job! A team obviously needs

both. But the simple truth is that you can't win a game without hittting the

back of the net with the ball. Here are some of the basic rules. All players

must be in their own half at the kick-off and the first touch of the ball must

go forward.

The game is restarted after a goal in exactly the same way, from the centre-spot, and also at the start of the second half. It is also allowed to score directly from the kick-off.

III.2 Game durations

All the football pundits say it, don't they? 'It only takes a second to score. That means there could be 5,400 goals in a game. Nonsense, of course, but the magic number is 90 - at senior level anyway. There are 90 magical minutes to score all those goals, which are split between two halves of 45 minutes. Then there is a break of up to 15 minutes at half-time for a breather and a chance for the manager to throw the tea cups about.

Additional time is allowed by the referee at the end of each half to make up for time lost through substitutions and treatment of injured players.

In cup competitions, extra-time is often played if the score is still level. Depending on the competition, this consists of two periods of no more than 15 minutes each. Still no goals after 30 minutes? Then it's down to the dreaded penalty shoot-out!

III.3 Football is all about scoring and stopping goals

But there are many different tactics that can be used in pursuit of these aims - and that's where the manager earns his crust.

It might be better to play more defensively to hold on to a lead.

Or, if the team is losing, a more attacking set-up that allows the players to push further forward may be required.

To alter the way the team is playing requires a change to the structure.

Traditionally, teams play in a 4-4-2 formation - that is four defenders, four midfielders and two strikers.

But, as the game has progressed and developed, managers and players have experimented with many variations of team formations.

Adaptability is the key and the best managers can change formations as the game progresses.

III.4 The most common formation you will likely see in British football is the 4-4-2

It's made up of four defenders, four midfielders and two strikers.

It is an adaptable system where you have strength in midfield and plenty of width.

Having two strikers means that the front line has extra support rather than having to wait for the midfield to reach them.

This formation, like others, tends to free up the full-backs, who will have more time on the ball than midfielders, particularly if the opposition is playing 4-4-2 as well.

In fact, some coaches see the two central midfielders in this formation as defenders and the full-backs as attackers.

This formation also offers the chance for one of the two central midfielders to get forward and support the strikers.

Sometimes the two midfielders will take turns in pushing forward to keep the defenders guessing.

But

some teams, such as

This gives the more attacking midfielder greater freedom to push forward and support the strikers.

This type of formation has been called the diamond formation as the four midfielders form a diamond-like shape, and it favours a team which does not have strong wingers.

III.5 Know your referee's signals?

![]()

When the referee starts waving his arms about

after blowing the whistle, do you know what he is indicating?

When the referee starts waving his arms about

after blowing the whistle, do you know what he is indicating?

He may be conducting himself in a medieval dance, but more likely he will be signalling a free-kick.

Here is our guide to the referee's signals:

DIRECT FREE-KICK

The referee should point with a raised arm in the direction that the free-kick has been given. The referee does need to make a further signal to indicate it is direct.Players often wait before taking a free-kick to check with the ref whether it is direct or indirect.

INDIRECT FREE-KICK

The referee will signal the positioning and direction of an indirect free-kick in the same way as any other free-kick. However, to show that the kick is indirect the referee keeps one arm outstretched above his head until after the kick is taken. It avoids any confusion when a goal is scored directly from a free-kick.

BOOKINGS

These are not the signals you should be wanting a ref to show you. The signal for a caution or sending off is the same - it's just the colour of the card that is different.The referee will take a note of the player and then hold the card high above the head with an outstretched arm.If the player is sent off for two bookable offences, the referee will show the second yellow card before holding up the red card.It is possible, though, that a player who has already been booked can be shown a straight red card.

When is a card red or yellow?

The different fouls that make the ref get out the red or yellow card

There are seven different offences that can get you a yellow card:

Anything that can be deemed as unsporting behaviour

Dissent by word or action

Persistent infringement of the laws, for example, a series of fouls

Delaying the restart of play

Not retreating the required distance at a free-kick or corner

Entering or re-entering the pitch without the referee's permission

Deliberately leaving the pitch without the referee's permission

A player is sent off and shown the red card if they commit any of the following seven offences:

Serious foul play

Violent conduct, such as throwing a punch

Spitting at an opponent or another person

A player other than the goalkeeper denying an obvious goalscoring opportunity by deliberately handling the ball

Denying an obvious goalscoring opportunity to an opponent moving towards the player's goal by an offence punishable by a free-kick or a penalty kick

Using offensive or insulting or abusive language and/or gestures

Receiving a second caution in the match

III. 6 Advantages

Even after a foul, a ref may allow play to continue sometimes. He will look to see if the team that would have been awarded the free-kick has an advantage in playing on.To signal that he is waving play on, he will extend both arms out in front of his body.

Know your referee assistant signals?

![]()

That

person on the touchline might look as though he's waving in some low flying

aircraft but those flags have a very important role

That

person on the touchline might look as though he's waving in some low flying

aircraft but those flags have a very important role

They used to be called linesmen but now they're referee assistants and they help the referee with offside decisions and signal a number of things, such as throw-ins and substitutions.So what are these signals? Well you don't need a degree in semaphore to understand what they all mean.

Here is our guide to the referee assistant signals:

THROW-IN

When the whole of the ball crosses the line, it's time for a throw-in.The assistant referee will hold up the flag in the direction that the team which is awarded the throw-in is attacking. The assistant will stand at the point where the ball crossed the line. But only if the ball goes out in the half of the pitch he is marshalling.

SUBSTITUTION

If the manager decides it's time to change the team then this is the signal you'll see on the touchline.The arms go up in the air and holding on to both sides of the flag, it is hung above the head of the referee's assistant.

Not the sort of signal you want to see if 30 seconds before you've just blazed a penalty over the bar.

OFFSIDE

There are three different signals for an offside. But the type of signal is dependent on where the offside offence is committed. The position where the assistant holds his flag makes it clear to the referee, players and spectators which player is being penalised for offside.

From the graphic above, here are the three scenarios:

1. FAR SIDE

The first signal is for offsides on the far side of the pitch. The assistant referee will hold the flag out in front of him at above head height.

2. CENTRE

The second signal indicates that a player in the centre of the pitch has strayed offside. The flag will be held out with an outstretched arm at shoulder height.

3. NEAR SIDE

If a player on the side of the pitch nearest to the assistant is deemed to be offside then the flag is pointed down towards the ground in front of the body.

Positions guide: who is in a team?

Regulation

football is played by two teams of 11 players but there is a variety of

formations that can be employed. In Premiership or League match, three subs

from a nominated five are allowed.

Regulation

football is played by two teams of 11 players but there is a variety of

formations that can be employed. In Premiership or League match, three subs

from a nominated five are allowed.

In the European competition, a manager can select from seven players on the bench. More can be used in friendlines.

![]() In

an 11-a-side match, a game cannot begin if either side has less than seven

players.

In

an 11-a-side match, a game cannot begin if either side has less than seven

players.

Football equipment guide

It's difficult to over emphasise the importance of having well fitted football boots

There is a huge variety of boots available at wildly varying prices, but the most expensive ones on the market won't necessarily be the best ones for you, and they certainly won't make you a better player.

So when you're choosing your next pair, forget style and think about practicality and comfort.

Firstly, try and understand the shape of your feet and your running style.

Also think about if you are flat-footed or have a high arch.

Ideally, football boots will fit snugly, although during teenage years with feet still growing it is advisable to allow some room to compensate.

CHAPTER IV

Short History

Manchester

United Football Club was first formed in 1878, albeit under a different name -

Newton Heath LYR (

Little suspecting the impact they were about to have on the national, even global game, the workers in the railway yard at Newton Heath indulged their passion for association football with games against other departments of the LYR or other railway companies.

Indeed, when the Football League was formed in 1888, Newton Heath did not consider themselves good enough to become founder members alongside the likes of Blackburn Rovers and Preston North End. They waited instead until 1892 to make their entrance.

Financial

problems plagued Newton Heath, and by the start of the twentieth century it

seemed they were destined for extinction. The club was saved, however, by a

local brewery owner, John Henry Davies. Legend has it that he learned of the

club's plight when he found a dog belonging to Newton Heath captain Harry

2000-2006

Manchester

United started the new decade, century and millennium in typical pioneering

fashion. They entered a brand new competition - the FIFA Club World

Championship in

The

January jaunt to

Several goalkeepers including Mark Bosnich tried and failed to establish themselves during the 1999/2000 season. So it was hardly surprising when Fabien Barthez joined United in July 2000, fresh from adding the European Championships crown to his World Cup winners medal.

The

eccentric but brilliant French goalkeeper helped United to win their third

successive title in 2000/01, a feat that had previously been achieved by only a

handful of clubs in

Sir Alex Ferguson had been at the helm for all three of United's back-to-back titles, and was therefore the first manager in English football to achieve the hat-trick. On the back of this latest trophy, Fergie announced he would be retiring from management at the end of the 2001/02 season - only to later change his mind and set about building another great side, this time to overcome Arsenal - the Premiership and FA Cup Double winners in May 2002.

Ferdinand helped the Reds to recapture their Premiership title in May 2003 but the calendar year ended on a low note for the defender - he was punished by the FA for failing to attend a mandatory drugs test at Carrington and was suspended for eight months from January to September 2004.

In

the period without Rio, the Reds lost their title - to Arsenal again - but won

the FA Cup for a record eleventh time, beating Millwall 3-0 in the 2004 final

at

Born: 11 Oct 1937

Signed: 01 Jun 1953

Debut: 6 Oct 1956 v Charlton (H) League

Goals Total: 249

Appearances Total: 759

![]() Position: Forward

Position: Forward

Left United: 1 May 1973

Nobody

embodies the values of Manchester United better than Sir Bobby Charlton. Having

survived the trauma of

In a 17-year playing career with United, he played a record 754 games, scoring 247 goals. It is unlikely his deeds will ever be matched. Although highly coveted by clubs across the country, the young Charlton, nephew of the great Newcastle United striker Jackie Milburn, turned professional with United in October 1954, winning the FA Youth Cup in 1954, 1955 and 1956.His league debut came on 6 October 1956 against Charlton at Old Trafford and the youngster made an immediate impact, scoring twice despite carrying an injury. "Mr Busby asked me if I was ok," recalled Sir Bobby. "I actually had a sprained ankle, but I wasn't going to admit to it and I crossed my fingers and said 'yes'."

Despite his dramatic bow, Charlton didn't command a relatively regular place until the latter stages of the 1956/57 season, notching 10 goals as the Busby Babes won a first title.

campaign as a right-back, but he later moved to his favoured position of centre-half. The positional switch suited Foulkes - he preferred to keep things simple, passing to his more gifted team-mates at the first opportunity. It was an approach that served him well.

CHAPTER V

CRICKET

The aim of cricket

Cricket is basically a simple game - score more than the opposition.

Two teams, both with 11 players, take it in turns to bat and bowl.

When one team is batting, they try and score as many runs as they can by hitting the ball around an oval field.

The other team must get them out by bowling the ball overarm at the stumps, which are at either end of a 22-yard area called a wicket.

The bowling team can get the batsmen out by hitting the stumps or catching the ball.

![]() Once

the batting team is all out, the teams swap over and they then become the

bowling side.

Once

the batting team is all out, the teams swap over and they then become the

bowling side.

Each time a team bats it is known as their innings. Teams can have one or two innings depending on how long there is to play.

The

Ashes Test matches are over five days so

Whoever scores the most runs wins. But a cricket match can be drawn too.

That happens when the team bowling last fails to get all the batsmen.

Two teams, both with 11 players, take it in turns to bat and bowl.

When one team is batting, they try and score as many runs as they can by hitting the ball around an oval field.

The other team must get them out by bowling the ball overarm at the stumps, which are at either end of a 22-yard area called a wicket.

The bowling team can get the batsmen out by hitting the stumps or catching the ball.

Once the batting team is all out, the teams swap over and they then become the bowling side.

Each time a team bats it is known as their innings. Teams can have one or two innings depending on how long there is to play.

The

Ashes Test matches are over five days so

Whoever scores the most runs wins. But a cricket match can be drawn too.

That happens when the team bowling last fails to get all the batsmen out.

How runs are scored

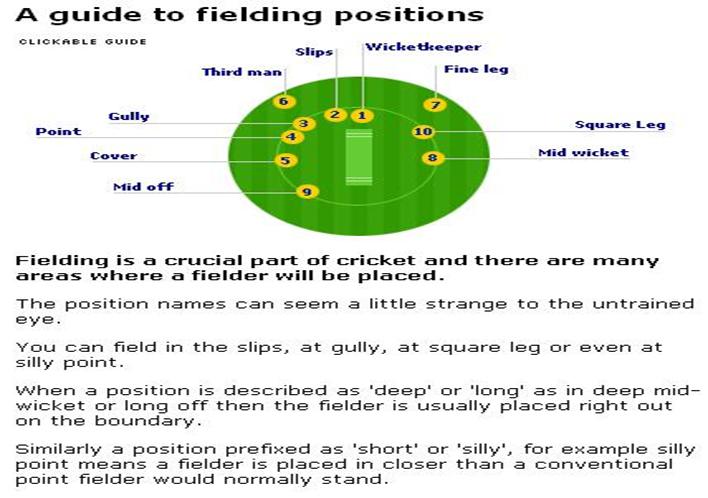

The fielding team has all 11 players on the field at the same time but there are only ever two batsmen.

Nine members of the fielding team can be positioned around the field depending on where the captain wants them.

![]() The

other two members of the team are the wicketkeeper and the bowler.

The

other two members of the team are the wicketkeeper and the bowler.

The bowler delivers the ball, overarm, at one of the batsmen who will try and hit the ball to score runs.

One run is scored each time the batsmen cross and reach the set of stumps at the other end of the pitch.

Four runs can be scored if the ball reaches the perimeter of the field or six runs if crosses the perimeter without bouncing. Although all 11 players have the chance to bat, the team is 'all out' when 10 wickets have fallen as the 'not out' batsman is left without a team-mate at the other end of the wicket.

A team doesn't have to be all out for an innings to close.

If a captain feels their team has scored enough runs, they can bring the innings to a close by making a 'declaration'.

Teams also have a '12th man' who acts as a substitute fielder if one of the first 11 is injured.

However, the 12th man is not allowed to bat or bowl, except in one-day cricket.

The difference between Test and one-day

International cricket is played in two different forms - Test matches and one-day games. Here are the key differences between the two.

The easiest way to tell Test and one-day cricket apart is by looking at the players. In Test cricket they always wear whites, whereas in the one-day game they wear colors.

The most important difference, however, is their respective lengths. Test cricket is played over five days, with each day's play lasting six hours and at least 90 overs bowled per-day.

One-day cricket - as its name suggests - is played on a single day and is restricted to a maximum number of overs.

Traditionally it lasts between 50 and 60 overs, however 20-over cricket has become more popular since the birth of the Twenty20 Cup.

In one-day cricket it's all about who can score the most runs in the same allotted amount of time.

Another key difference is that in the longer form each team has two turns to bat (called innings).

Each innings is over when either ten batsmen are out (all out), or the captain of the batting side declares the innings finished, for tactical reasons.

In one day cricket, on the other hand, the teams bat just once and an innings is over when either ten batsmen are out or all the overs have been bowled.

Understanding byes and leg byes

If a legitimate ball passes the batsman without touching his bat or his body, any runs completed are credited as 'byes'.

If a legitimate ball misses the bat but touches the batsman's body, any runs completed are credited as 'leg byes'.

Runs completed off a bye or leg byes, including boundaries, are added to the extras tally of the batting team but they are not credited against the bowler. In order for a leg bye to be awarded the umpire must deem that the batsman either attempted to play a stroke or tried to avoid being hit by the ball.

If the umpire considers that the batsman did neither of these then a dead ball is called and no runs can be scored.

The field of play

The size of the field on which the game is played varies from ground to ground but the pitch always stays the same. It is a rectangular area of 22 yards (20.12m) in length and 10ft (3.05m) in width. The popping (batting) crease is marked 1.22m in front of the stumps at either end, with the stumps set along the bowling crease.

The return creases are marked at right angles to the popping and bowling creases and are measured 1.32m either side of the middle stumps.

The two sets of wickets at opposite ends of the pitch stand 71.1cm high and three stumps measure 22.86 cm wide in total.

Made out of willow the stumps have two bails on top and the wicket is only broken if at least one bail is removed.

If the ball hits the wicket but without knocking a bail off, then the batsman is not out.

Do you get confused by cricketing slang? If so, wonder no more after reading our A-Z guide to the jargon.

BITE

The amount of turn a spinner is able to extract from a particular wicket. And once Murali gets his teeth into you, it is definitely a case of once bitten, twice shy.

BLOCK

Defensive batting stroke expertly played by Geoff Boycott, whose repetitive blocking tactics often sent fielders to sleep, enabling him to cut loose.

BOUNCER

Ugly brute of a delivery - quick, short and designed to take the batsman's head off if he doesn't take evasive action. Not to be confused with bouncer - ugly brute designed to take your head off.

CHINAMAN

A deceptive delivery from a left-arm spinner, which fools the batsman into thinking it will spin from off to leg and does the opposite. May cause him to cry: 'Well I'm a Dutchman!' Possibly.

DRIVE

Attacking, punchy, front-foot shot straight down the ground or through the covers. Michael Vaughan is one of the best drivers in the business - along with Michael Schumacher.

DUCK

A batsman removed from the attack without troubling the scorers. So called (perhaps) because a duck's egg is shaped like a zero. Plus it sounds better than hen. A golden duck is when this fate falls upon the batsman on his very first bowl.

FEATHER

The faintest of edges from a batsman - often resulting in a catch behind. Also known as a tickle.

FLIPPER

An underhand delivery used by a leg-spin bowler which comes at the batsman faster than a standard ball, with backspin. Gets Shane Warne's seal of approval.

FULL TOSS

A bowling delivery that reaches the batsman without bouncing - usually despatched for four. Unlike the beamer, which just takes your head off on its way through.

GARDENING

A batsman prodding down loose areas of the pitch with the end of his bat. In Glenn McGrath's case, it means planting seeds of doubt in the batsman's mind before uprooting his wicket.

GOOGLY

A leg spinner's prize weapon bowled out of the back of the hand. It looks like a normal leg spinner but turns towards the batsman, like an off break, rather than away from the bat.

GRUBBER

A delivery that keeps low after leaving the bowler's hand. So called because it inches along the ground - and then turns into a butterfly. OK, we made that last bit up.

HOOK

A reflex action shot to the onside aimed at keeping a short ball from smacking you plum in the face. Ian Botham often used to play it with his eyes closed.

An unplayable delivery - think Shane Warne's 'Ball of the Century' to remove Mike Gatting at Old Trafford in 1993. Less effective when using an orange, obviously.

MAIDEN

When an over is bowled and no runs are scored from it. Rumoured to take its name from a beautiful woman, who 'bowled' over a young cricketer.

PAD

A protective covering for the legs of the batsmen and wicketkeeper. If a cricketer ever suggests 'Your pad or mine', check what he's after before uttering your reply.

PIE THROWER

An inferior bowler, one who bowls like a clown throwing a pie. Not to be confused with the likes of Merv Hughes and Mike Gatting, who were, of course, famed pie-eaters.

PLUMB

The perfect lbw. When the ball hits a batsman on the leg directly in front of the stumps. One might also describe it as a peach of a delivery, although a pair is a different thing altogether.

SESSION

A period of play during a match - eg morning, afternoon, evening sessions. If, however, you are a spectator, you will only experience one period - the all-day session.

SLEDGING

To

tell your opponent what you think about him in a less than complimentary

fashion. One of the most legendary examples features Glenn McGrath, Mrs

McGrath,

SILLY

Any fielding position where you are extremely close to the batsman and in danger of being injured. When the captain orders you to silly mid-off, you know he's got a new favourite.

CHAPTER VI

SNOOKER

VI 1.History

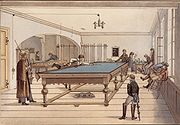

Figure 10. Snooker table

Illustration

of a game of three ball pocket billiards in early 19th

century Tbingen,

It

thus became attached to the billiards game now bearing its name as inexperienced

players were labelled as snookers. The game of snooker grew in the latter half

of the 19th century and the early 20th century, and by the

first World Snooker

Championship had been organised by Joe Davis who, as a professional English billiards and snooker player, moved the

game from a pastime activity into a more professional sphere.

Joe Davis won every world championship until 1946 when he retired. The game

went into a decline through the 1950s and 1960s with little interest generated

outside of those who played. In 1959,

However, it never caught on. A major advance

occurred in 1969, when David Attenborough who was then

a top official of the BBC, commissioned the snooker tournament Pot Black to demonstrate the potential of colour television,

with the green table and multi-coloured balls being ideal for showing off the

advantages of colour broadcasting. The TV series became a ratings success and

was for a time the second most popular show on BBC Two. Interest in the game increased and the 1978 World

Championship was the first to be fully televised. The game quickly

became a mainstream sport in the

In recent years the loss of tobacco sponsorship has led to a decrease in the number of professional tournaments, although some new sponsors have been sourced; and the popularity of the game in the Far East and China, with emerging talents such as Liang Wenbo and more established players such as Ding Junhui and Marco Fu, bodes well for the future of the sport in that part of the world.

Figure 11.The ''White Ball''

![]() The

object of the game is to score more points

than the opponent by potting object balls

in a predefined order. At the start of a frame, the balls are positioned as

shown and the players take it in turns to hit a shot in a single strike from

the tip of the

cue, their aim being to pot one of the red balls

and score a point. If they do pot at least one red, then it remains in the

pocket and they are allowed another shot - this time the aim being to pot one

of the colours. If successful, then they gain the value of the colour potted.

It is returned to its correct position on the table and they must try to pot

another red again. This process continues until they fail to pot the desired

ball, at which point their opponent comes back to the table to play the next

shot. The game continues in this manner until all the reds are potted and only

the 6 colours are left on the table; at that point the aim is then to pot the

colours in the order yellow, green, brown, blue, pink, black. When a colour is

potted in this phase of a frame, it remains off the table. When the final ball

is potted, the player with the most points wins.

The

object of the game is to score more points

than the opponent by potting object balls

in a predefined order. At the start of a frame, the balls are positioned as

shown and the players take it in turns to hit a shot in a single strike from

the tip of the

cue, their aim being to pot one of the red balls

and score a point. If they do pot at least one red, then it remains in the

pocket and they are allowed another shot - this time the aim being to pot one

of the colours. If successful, then they gain the value of the colour potted.

It is returned to its correct position on the table and they must try to pot

another red again. This process continues until they fail to pot the desired

ball, at which point their opponent comes back to the table to play the next

shot. The game continues in this manner until all the reds are potted and only

the 6 colours are left on the table; at that point the aim is then to pot the

colours in the order yellow, green, brown, blue, pink, black. When a colour is

potted in this phase of a frame, it remains off the table. When the final ball

is potted, the player with the most points wins.

Points may also be scored in a game when a player's opponent fouls. A foul can occur for numerous reasons, such as hitting a colour first when the player was attempting to hit a red, potting the cue ball, or failing to escape from 'a snooker' (a situation where the previous player finished their turn leaving the cue ball in a position where the object ball cannot be hit directly). Points gained from a foul vary from a minimum of 4 to a maximum of 7 if the black ball is involved. One game, from the balls in their starting position until the last ball is potted, is called a frame. A match generally consists of a predefined number of frames and the player who wins the most frames wins the match overall.

Most professional matches require a player to win five frames, and are called 'Best of Nine' as that is the maximum possible number of frames. Tournament finals are usually best of 17 or best of 19, while the World Championship uses longer matches - ranging from best of 19 in the qualifiers and the first round proper, up to 35 frames in length (first to 18), and is played over two days. Professional and competitive amateur matches are officiated by a referee who is the sole judge of fair play.

The referee also respots the colours on to the table and calls out how many points the player has scored during a break. Professional players usually play the game in a sporting manner, declaring fouls the referee has missed, acknowledging good shots from their opponent, or holding up a hand to apologise for fortunate shots.

Figure 12. Snooker bat

An extended spider, which can be used to bridge over balls obstructing a shot that is too far away to be bridged by hand

Other terminology used in snooker includes a player's break, which refers to the total number of consecutive points a player has amassed (excluding fouls) when at one visit to the table. A player attaining a break of 15, for example, could have reached it by potting a red then a black, then a red then a pink, before failing to pot the next red. The traditional maximum break in snooker is to pot all reds with blacks then all colours, which would yield 147 points; this is often known as a '147' or a 'maximum' .See also: Highest snooker breaks.

Accessories used for snooker include chalk for the tip of the cue, rests of various sorts (needed often, due to the length of a full-size table), a triangle to rack the reds, and a scoreboard. One drawback of snooker on a full-size table is the size of the room (22' x 16' or approximately 5 m x 7 m), which is the minimum required for comfortable cueing room on all sides. This limits the number of locations in which the game can easily be played. While pool tables are common to many pubs, snooker tends to be played either in private surroundings or in public snooker halls. The game can also be played on smaller tables using fewer red balls. The variants in table size are: 10' x 5', 9' x 4.5', 8' x 4', 6' x 3' (the smallest for realistic play) and 4' x 2'. Smaller tables can come in a variety of styles, such as fold away or dining-table convertible.

VI 2.Governance and tournaments

Figure 13. Snooker tournament

Action from The Masters Tournament in 2007

|

|

|

Ranking tournaments |

|

World Championship |

|

UK Championship |

|

Grand Prix |

|

Welsh Open |

|

China Open |

|

Shanghai Masters |

|

Northern Ireland Trophy |

|

Bahrain Championship |

|

Other tournaments |

|

Masters |

|

Premier League |

|

Pot Black |

|

World Series of Snooker |

|

Malta Cup |

|

Withdrawn tournaments |

The

World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association

(WPBSA, also known as World Snooker), founded in 1968 as the Professional

Billiard Players' Association, is the governing body for the professional game.

Its subsidiary, World Snooker, based in Bristol,

Professional snooker players can play on the World Snooker main tour ranking circuit. Ranking points, earned by players through their performances over the previous two seasons, determine the current world ranking. A player's ranking determines what level of qualification they require for ranking tournaments. The elite of professional snooker is generally regarded as the 'Top 16' ranking players, who are not required to pre-qualify for any of the tournaments. The tour contains 96 players - the top 64 from the previous two seasons, the 8 highest one-year point scorers who are not in the top 64, the top 8 from the previous season's Challenge Tour, and various regional, junior and amateur champions.

The

most important event in professional snooker is the World Championship,

held annually since 1927 (except during the Second World War and between 1958 and 1963). The

tournament has been held at the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield (

The group of tournaments that come next in importance are the other ranking tournaments. Players in these tournaments score world ranking points. A high ranking ensures qualification for next year's tournaments, invitations to invitational tournaments and an advantageous draw in tournaments. The most prestigious of these after the World Championship is the UK Championship. Third in line are the invitational tournaments, to which most of the highest ranked players are invited. The most important tournament in this category is The Masters, which to most players is the second or third most sought-after prize.

In

an attempt to answer criticisms that televised matches can be slow or get

bogged down in lengthy safety exchanges and that long matches causes problems

for advertisers, an alternative series of timed tournaments has been organised

by Matchroom Sport Chairman Barry Hearn. The shot-timed Betfred Premier

League was established, with the top eight players in the world

invited to compete at regular

There are also other tournaments that have less importance, earn no world ranking points and are not televised. These can change on a year-to-year basis depending on calendars and sponsors. Currently the Pontin's International Open Series is organized as one of these additional tournament series by World Snooker.

VI 3.List of snooker equipment

Chalk

The tip of the cue is 'chalked' to ensure good contact between the cue and the cue-ball.

Cue

A stick, made of wood or fibreglass, the tip of which is used to strike the cue-ball.

Extension

A shorter baton that fits over, or screws into, the back end of the cue, effectively lengthening it. Is used for shots where the cue-ball is a long distance from the player.

Rest

A stick with an X-shaped head that is used to support the cue when the cue ball is out of reach at normal extension.

Hook rest

Identical to the normal rest, yet with a hooked metal end. It is used to set the rest around another ball. The hook rest is the most recent invention in snooker.

Spider

Similar to the rest but with an arch-shaped head; it is used to elevate and support the tip of the cue above the height of the cue-ball.

Swan (or swan-neck spider)

This equipment, consisting of a rest with a single extended neck and a fork-like prong at the end, is used to give extra cueing distance over a group of balls.

Triangle/Rack

The piece of equipment is used for gathering the red balls into the formation required for the break to start a frame.

Extended rest

Similar to the regular rest, but with a mechanism at the butt end which makes it possible to extend the rest by up to three feet.

Extended spider

A hybrid of the swan and the spider. Its purpose is to bridge over large packs of reds. Is less common these days in professional snooker but can be used in situations where the position of one or more balls prevents the spider being placed where the striker desires.

Ball marker

A multi-purpose instrument with a 'D' shaped notch, which a referee can (1) place next to a ball, in order to mark the position of it. They can then remove the ball to clean it; (2) use to judge if a ball is preventing a colour from being placed on its spot; (3) use to judge if the cue ball can hit the extreme edge of a 'ball on' when awarding a free ball (by placing it alongside the potentially intervening ball).

CHAPTER VII

HORSE RACING

VII1.TheHistoryofHorseRacing

Figure 14. Horse Racing

The

competitive racing of horses is one of humankind's most ancient sports, having

its origins among the prehistoric nomadic tribesmen of

Horse

racing is the second most widely attended

![]() By far the most popular form of the sport is

the racing of mounted THOROUGHBRED horses over flat courses at distances from

three-quarters of a mile to two miles. Other major forms of horse racing are

harness racing, steeplechase racing, and QUARTER HORSE racing.

By far the most popular form of the sport is

the racing of mounted THOROUGHBRED horses over flat courses at distances from

three-quarters of a mile to two miles. Other major forms of horse racing are

harness racing, steeplechase racing, and QUARTER HORSE racing.

VII.2 Thoroughbred Racing

By

the time humans began to keep written records, horse racing was an organized

sport in all major civilizations from Central Asia to the

![]() The origins of modern racing lie in the 12th

century, when English knights returned from the Crusades with swift Arab

horses. Over the next 400 years, an increasing number of Arab stallions were

imported and bred to English mares to produce horses that combined speed and

endurance. Matching the fastest of these animals in two-horse races for a

private wager became a popular diversion of the nobility.

The origins of modern racing lie in the 12th

century, when English knights returned from the Crusades with swift Arab

horses. Over the next 400 years, an increasing number of Arab stallions were

imported and bred to English mares to produce horses that combined speed and

endurance. Matching the fastest of these animals in two-horse races for a

private wager became a popular diversion of the nobility.

![]() Horse racing began to become a professional

sport during the reign (1702-14) of Queen Anne, when match racing gave way to

races involving several horses on which the spectators wagered. Racecourses

sprang up all over

Horse racing began to become a professional

sport during the reign (1702-14) of Queen Anne, when match racing gave way to

races involving several horses on which the spectators wagered. Racecourses

sprang up all over

![]() The Jockey Club wrote complete rules of

racing and sanctioned racecourses to conduct meetings under those rules.

Standards defining the quality of races soon led to the designation of certain

races as the ultimate tests of excellence. Since 1814, five races for

three-year-old horses have been designated as 'classics.' Three

races, open to male horses (colts) and female horses (fillies), make up the

English Triple Crown: the 2,000

The Jockey Club wrote complete rules of

racing and sanctioned racecourses to conduct meetings under those rules.

Standards defining the quality of races soon led to the designation of certain

races as the ultimate tests of excellence. Since 1814, five races for

three-year-old horses have been designated as 'classics.' Three

races, open to male horses (colts) and female horses (fillies), make up the

English Triple Crown: the 2,000

![]() The Jockey Club also took steps to regulate

the breeding of racehorses. James Weatherby, whose family served as accountants

to the members of the Jockey Club, was assigned the task of tracing the

pedigree, or complete family history, of every horse racing in

The Jockey Club also took steps to regulate

the breeding of racehorses. James Weatherby, whose family served as accountants

to the members of the Jockey Club, was assigned the task of tracing the

pedigree, or complete family history, of every horse racing in

VII 3.American Thoroughbred Racing

The

British settlers brought horses and horse racing with them to the New World,

with the first racetrack laid out on

![]() The rapid growth of the sport without any

central governing authority led to the domination of many tracks by criminal

elements. In 1894 the nation's most prominent track and stable owners met in

The rapid growth of the sport without any

central governing authority led to the domination of many tracks by criminal

elements. In 1894 the nation's most prominent track and stable owners met in

![]() In the early 1900s, however, racing in the

In the early 1900s, however, racing in the

![]() Thoroughbred tracks exist in about half the

states. Public interest in the sport focuses primarily on major Thoroughbred

races such as the American Triple Crown and the Breeder's Cup races (begun in

1984), which offer purses of up to about $1,000,000. State racing commissions

have sole authority to license participants and grant racing dates, while

sharing the appointment of racing officials and the supervision of racing rules

with the Jockey Club. The Jockey Club retainsauthority over the breedin.

Thoroughbred tracks exist in about half the

states. Public interest in the sport focuses primarily on major Thoroughbred

races such as the American Triple Crown and the Breeder's Cup races (begun in

1984), which offer purses of up to about $1,000,000. State racing commissions

have sole authority to license participants and grant racing dates, while

sharing the appointment of racing officials and the supervision of racing rules

with the Jockey Club. The Jockey Club retainsauthority over the breedin.

Figure 15. Horses

VII 4.Breeding

Although science has been unable to come up with any breeding system that guarantees the birth of a champion, breeders over the centuries have produced an increasingly higher percentage of Thoroughbreds who are successful on the racetrack by following two basic principles. The first is that Thoroughbreds with superior racing ability are more likely to produce offspring with superior racing ability. The second is that horses with certain pedigrees are more likely to pass along their racing ability to their offspring.

![]() Male Thoroughbreds (stallions) have the

highest breeding value because they can mate with about 40 mares a year. The

worth of champions, especially winners of Triple Crown races, is so high that

groups of investors called breeding syndicates may be formed. Each of the

approximately 40 shares of the syndicate entitles its owner to breed one mare

to the stallion each year. One share, for a great horse, may cost several

million dollars. A share's owner may resell that share at any time.

Male Thoroughbreds (stallions) have the

highest breeding value because they can mate with about 40 mares a year. The

worth of champions, especially winners of Triple Crown races, is so high that

groups of investors called breeding syndicates may be formed. Each of the

approximately 40 shares of the syndicate entitles its owner to breed one mare

to the stallion each year. One share, for a great horse, may cost several

million dollars. A share's owner may resell that share at any time.

![]() Farms that produce foals for sale at auction

are called commercial breeders. The most successful are E. J. Taylor,

Spendthrift Farms, Claiborne Farms, Gainsworthy Farm, and Bluegrass Farm, all

in

Farms that produce foals for sale at auction

are called commercial breeders. The most successful are E. J. Taylor,

Spendthrift Farms, Claiborne Farms, Gainsworthy Farm, and Bluegrass Farm, all

in

VII 5.Betting

Figure 16. Horse Betting

Wagering on the outcome of horse races has been an integral part of the appeal of the sport since prehistory and today is the sole reason horse racing has survived as a major professional sport.

![]() All betting at American tracks today is done

under the pari-mutuel wagering system, which was developed by a Frenchman named

Pierre Oller in the late 19th century. Under this system, a fixed percentage

(14 percent-25 percent) of the total amount wagered is taken out for track

operating expenses, racing purses, and state and local taxes. The remaining sum

is divided by the number of individual wagers to determine the payoff, or

return on each bet. The projected payoff, or 'odds,' are continuously

calculated by the track's computers and posted on the track odds board during

the betting period before each race. Odds of '2-1,' for example, mean

that the bettor will receive $2 profit for every $1 wagered if his or her horse

wins.

All betting at American tracks today is done

under the pari-mutuel wagering system, which was developed by a Frenchman named

Pierre Oller in the late 19th century. Under this system, a fixed percentage

(14 percent-25 percent) of the total amount wagered is taken out for track

operating expenses, racing purses, and state and local taxes. The remaining sum

is divided by the number of individual wagers to determine the payoff, or

return on each bet. The projected payoff, or 'odds,' are continuously

calculated by the track's computers and posted on the track odds board during

the betting period before each race. Odds of '2-1,' for example, mean

that the bettor will receive $2 profit for every $1 wagered if his or her horse

wins.

![]() At all tracks, bettors may wager on a horse

to win (finish first), place (finish first or second), or show (finish first,

second, or third). Other popular wagers are the daily double (picking the

winners of two consecutive races), exactas (picking the first and second horses

in order), quinellas (picking the first and second horses in either order), and

the pick six (picking the winners of six consecutive races).

At all tracks, bettors may wager on a horse

to win (finish first), place (finish first or second), or show (finish first,

second, or third). Other popular wagers are the daily double (picking the

winners of two consecutive races), exactas (picking the first and second horses

in order), quinellas (picking the first and second horses in either order), and

the pick six (picking the winners of six consecutive races).

VII 6.Handicapping

The difficult art of predicting the winner of a horse race is called handicapping. The process of handicapping involves evaluating the demonstrated abilities of a horse in light of the conditions under which it will be racing on a given day. To gauge these abilities, handicappers use past performances, detailed published records of preceding races. These past performances indicate the horse's speed, its ability to win, and whether the performances tend to be getting better or worse. The conditions under which the horse will be racing include the quality of the competition in the race, the distance of the race, the type of racing surface (dirt or grass), and the current state of that surface (fast, sloppy, and so on). The term handicapping also has a related but somewhat different meaning: in some races, varying amounts of extra weight are assigned to horses based on age or ability in order to equalize the field.

VII 7.Harness Racing

The

racing of horses in harness dates back to ancient times, but the sport

virtually disappeared with the fall of the

With

the popularity of harness racing came the development of the STANDARDBRED, a

horse bred specifically for racing under harness. The founding sire of all

Standardbreds is an English Thoroughbred named Messenger, who was brought to

the

![]() Harness racing reached the early zenith of

its popularity in the late 1800s, with the establishment of a Grand Circuit of

major fairs. The sport sharply declined in popularity after 1900, as the

automobile replaced the horse and the

Harness racing reached the early zenith of

its popularity in the late 1800s, with the establishment of a Grand Circuit of

major fairs. The sport sharply declined in popularity after 1900, as the

automobile replaced the horse and the

VII 8.Steeplechase, Hurdle, and Point-To-Point Racing

Steeplechases

are races over a 2- to 4-mi (3.2- to 6.4-km) course that includes such

obstacles as brush fences, stone walls, timber rails, and water jumps. The

sport developed from the English and Irish pastime of fox hunting, when hunters

would test the speed of their mounts during the cross-country chase. Organized

steeplechase racing began about 1830, and has continued to be a popular sport

in

![]() Hurdling is a form of steeplechasing that is

less physically demanding of the horses. The obstacles consist solely of

hurdles 1 to 2 ft (0.3 to 0.6 m) lower than the obstacles on a steeplechase course,

and the races are normally less than 2 mi in length. Hurdling races are often

used for training horses that will later compete in steeplechases. Horses

chosen for steeplechase training are usually Thoroughbreds selected for their

endurance, calm temperament, and larger-than-normal size.

Hurdling is a form of steeplechasing that is

less physically demanding of the horses. The obstacles consist solely of

hurdles 1 to 2 ft (0.3 to 0.6 m) lower than the obstacles on a steeplechase course,

and the races are normally less than 2 mi in length. Hurdling races are often

used for training horses that will later compete in steeplechases. Horses

chosen for steeplechase training are usually Thoroughbreds selected for their

endurance, calm temperament, and larger-than-normal size.

![]() Point-to-point races are held for amateurs on

about 120 courses throughout the

Point-to-point races are held for amateurs on

about 120 courses throughout the

Conclusions

In my point of

view

The sports that they've created for us is not just some usual sports.it can be also a job for us thay is paid very good.

Sport is very important for us, for our health as we always want to progress, to attain some kind of performance. Practicing a sport we will have a healthy body and a strong mind.

Also from sports we can bring the best behavior from us ,to be an example ,to accive something .

For me an tipical

sport that

Bibliography

|

Politica de confidentialitate | Termeni si conditii de utilizare |

Vizualizari: 3649

Importanta: ![]()

Termeni si conditii de utilizare | Contact

© SCRIGROUP 2026 . All rights reserved