Limba Engleza

Thomas Alva Edison

Introduction

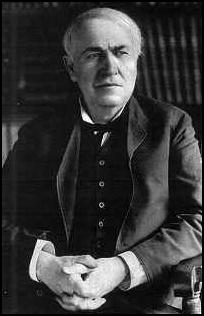

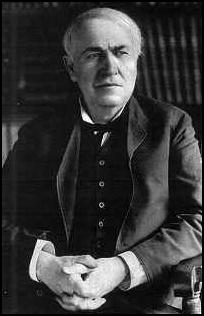

Thomas

Alva Edison (February 11, 1847 - October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and

businessman who developed many devices which greatly influenced life around the

world. Dubbed 'The Wizard of Menlo Park' by a newspaper reporter, he

was one of the first inventors to apply the principles of mass production to

the process of invention, and therefore is often credited with the creation of

the first industrial research laboratory.

Some

of his inventions were not completely original but amounted to improvements of

earlier inventions. Also, many of the inventions attributed to him were

actually created by one or more of the numerous employees working under his

direction. Nevertheless, Edison is considered one of the most prolific

inventors in history, holding 1,097 U.S.

patents in his name, as well as many patents in the United

Kingdom, France

and Germany.

Structured

in three chapters, the paper starts by describing Thomas Edison's life bla bla .

The second chapter presents all his important inventions and the third chapter makes a walk through

his failed inventions.

The reason why I have chosen this

subject is because Thomas Edison was more responsible than any one else for

creating the modern world . No one

did more too shape the physical/cultural makeup of present day

civilization. Accordingly, he was the most influential figure of the

millennium.'

The Life of Thomas Edison

Thomas

Alva Edison was born on February 11, 1847 in Milan, Ohio; the seventh

and last child of Samuel and Nancy Edison. When Edison was seven his family

moved to Port Huron, Michigan. Edison

lived here until he struck out on his own at the age of sixteen. Edison had very little formal education as a child,

attending school only for a few months. He was taught reading, writing, and

arithmetic by his mother, but was always a very curious child and taught

himself much by reading on his own. This belief in self-improvement remained

throughout his life.

Edison began working at an early age, as most boys did at

the time. At thirteen he took a job as a newsboy, selling newspapers and candy

on the local railroad that ran through Port Huron

to Detroit. He

seems to have spent much of his free time reading scientific, and technical

books, and also had the opportunity at this time to learn how to operate a

telegraph. By the time he was sixteen, Edison

was proficient enough to work as a telegrapher full time.

The

development of the telegraph was the first step in the communication

revolution, and the telegraph industry expanded rapidly in the second half of

the 19th century. This rapid growth gave Edison

and others like him a chance to travel, see the country, and gain experience.

Edison worked in a number of cities throughout the United

States before arriving in Boston in 1868. Here Edison

began to change his profession from telegrapher to inventor. He received his

first patent on an electric vote recorder, a device intended for use by elected

bodies such as Congress to speed the voting process. This invention was a

commercial failure. Edison resolved that in

the future he would only invent things that he was certain the public would

want.

Edison

moved to New York City

in 1869. He continued to work on inventions related to the telegraph, and

developed his first successful invention, an improved stock ticker called the

'Universal Stock Printer'. For this and some related inventions Edison was paid $40,000. This gave Edison the money he

needed to set up his first small laboratory and manufacturing facility in Newark, New

Jersey in 1871. During the next five years, Edison

worked in Newark

inventing and manufacturing devices that greatly improved the speed and

efficiency of the telegraph. He also found to time to get married to Mary

Stilwell and start a family.

In

1876 Edison sold all his Newark manufacturing

concerns and moved his family and staff of assistants to the small village of Menlo Park,

twenty-five miles southwest of New

York City. Edison

established a new facility containing all the equipment necessary to work on

any invention. This research and development laboratory was the first of its

kind anywhere; the model for later, modern facilities such as Bell

Laboratories, this is sometimes considered to be Edison's

greatest invention. Here Edison began to

change the world.

The

first great invention developed by Edison in Menlo Park was the tin foil phonograph. The

first machine that could record and reproduce sound created a sensation  and brought Edison international fame. Edison

toured the country with the tin foil phonograph, and was invited to the White

House to demonstrate it to President Rutherford B. Hayes in April 1878.

and brought Edison international fame. Edison

toured the country with the tin foil phonograph, and was invited to the White

House to demonstrate it to President Rutherford B. Hayes in April 1878.

Edison next undertook his greatest challenge, the

development of a practical incandescent, electric light. The idea of electric

lighting was not new, and a number of people had worked on, and even developed

forms of electric lighting. But up to that time, nothing had been developed

that was remotely practical for home use. Edison's

eventual achievement was inventing not just an incandescent electric light, but

also an electric lighting system that contained all the elements necessary to

make the incandescent light practical, safe, and economical. After one and a

half years of work, success was achieved when an incandescent lamp with a

filament of carbonized sewing thread burned for thirteen and a half hours. The

first public demonstration of the Edison's incandescent lighting system was in

December 1879, when the Menlo Park

laboratory complex was electrically lighted. Edison

spent the next several years creating the electric industry. In September 1882,

the first commercial power station, located on Pearl Street in lower Manhattan, went into operation providing

light and power to customers in a one square mile area; the electric age had

begun.

Edison next undertook his greatest challenge, the

development of a practical incandescent, electric light. The idea of electric

lighting was not new, and a number of people had worked on, and even developed

forms of electric lighting. But up to that time, nothing had been developed

that was remotely practical for home use. Edison's

eventual achievement was inventing not just an incandescent electric light, but

also an electric lighting system that contained all the elements necessary to

make the incandescent light practical, safe, and economical. After one and a

half years of work, success was achieved when an incandescent lamp with a

filament of carbonized sewing thread burned for thirteen and a half hours. The

first public demonstration of the Edison's incandescent lighting system was in

December 1879, when the Menlo Park

laboratory complex was electrically lighted. Edison

spent the next several years creating the electric industry. In September 1882,

the first commercial power station, located on Pearl Street in lower Manhattan, went into operation providing

light and power to customers in a one square mile area; the electric age had

begun.

The success of his electric light

brought Edison to new heights of fame and

wealth, as electricity spread around the world. Edison's

various electric companies continued to grow until in 1889 they were brought

together to form Edison General Electric. Despite the use of Edison in the

company title however, Edison never controlled

this company. The tremendous amount of capital needed to develop the

incandescent lighting industry had necessitated the involvement of investment

bankers such as J.P. Morgan. When Edison General Electric merged with its

leading competitor Thompson-Houston in 1892, Edison

was dropped from the name, and the company became simply General Electric.

The success of his electric light

brought Edison to new heights of fame and

wealth, as electricity spread around the world. Edison's

various electric companies continued to grow until in 1889 they were brought

together to form Edison General Electric. Despite the use of Edison in the

company title however, Edison never controlled

this company. The tremendous amount of capital needed to develop the

incandescent lighting industry had necessitated the involvement of investment

bankers such as J.P. Morgan. When Edison General Electric merged with its

leading competitor Thompson-Houston in 1892, Edison

was dropped from the name, and the company became simply General Electric.

This

period of success was marred by the death of Edison's

wife Mary in 1884. Edison's involvement in the business end of the electric industry

had caused Edison to spend less time in Menlo

Park. After Mary's death, Edison was there even less,

living instead in New York City

with his three children. A year later, while vacationing at a friends house in

New England, Edison met Mina Miller and fell

in love. The couple was married in February 1886 and moved to West

Orange, New Jersey where Edison had purchased an estate, Glenmont, for his bride.

Thomas Edison lived here with Mina until his death.

When

Edison moved to West Orange, he was doing experimental work in makeshift

facilities in his electric lamp factory in nearby Harrison, New Jersey.

A few months after his marriage, however, Edison decided to build a new

laboratory in West Orange itself, less than a

mile from his home. Edison possessed the both the resources and experience by

this time to build, 'the best equipped and largest laboratory extant and

the facilities superior to any other for rapid and cheap development of an

invention '. The new laboratory complex consisting of five buildings

opened in November 1887. A three story main laboratory building contained a

power plant, machine shops, stock rooms, experimental rooms and a large

library. Four smaller one story buildings built perpendicular to the main

building contained a physics lab, chemistry lab, metallurgy lab, pattern shop,

and chemical storage. The large size of the laboratory not only allowed Edison to work on any sort of project, but also allowed

him to work on as many as ten or twenty projects at once. Facilities were added

to the laboratory or modified to meet Edison's

changing needs as he continued to work in this complex until his death in 1931.

Over the years, factories to manufacture Edison

inventions were built around the laboratory. The entire laboratory and factory

complex eventually covered more than twenty acres and employed 10,000 people at

its peak during World War One (1914-1918).

After

opening the new laboratory, Edison began to

work on the phonograph again, having set the project aside to develop the electric

light in the late 1870s. By the 1890s, Edison

began to manufacture phonographs for both home, and business use. Like the

electric light, Edison developed everything

needed to have a phonograph work, including records to play, equipment to

record the records, and equipment to manufacture the records and the machines.

In the process of making the phonograph practical, Edison

created the recording industry. The development and improvement of the

phonograph was an ongoing project, continuing almost until Edison's

death.

The Inventions of Thomas Edison

The Inventions of Thomas Edison

Phonograph

- History

The

first great invention developed by Edison in Menlo Park was the tin foil phonograph. While

working to improve the efficiency of a telegraph transmitter, he noted that the

tape of the machine gave off a noise resembling spoken words when played at a

high speed. This caused him to wonder if he could record a telephone message.

He began experimenting with the diaphragm of a telephone receiver by attaching

a needle to it. He reasoned that the needle could prick paper tape to record a

message. His experiments led him to try a stylus on a tinfoil cylinder, which,

to his great surprise, played back the short message he recorded, 'Mary

had a little lamb.'

The

word phonograph was the trade name for Edison's

device, which played cylinders rather than discs. The machine had two needles:

one for recording and one for playback. When you spoke into the mouthpiece, the

sound vibrations of your voice would be indented onto the cylinder by the

recording needle. This cylinder phonograph was the first machine that could

record and reproduce sound created a sensation and brought Edison

international fame.

August

12, 1877, is the date popularly given for Edison's

completion of the model for the first phonograph. It is more likely, however,

that work on the model was not finished until November or December of that

year, since he did not file for the patent until December 24, 1877. He toured

the country with the tin foil phonograph, and was invited to the White House to

demonstrate it to President Rutherford B. Hayes in April 1878.

In

1878, Thomas Edison established the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company to sell

the new machine. He suggested other uses for the phonograph, such as: letter

writing and dictation, phonographic books for blind people, a family record

(recording family members in their own voices), music boxes and toys, clocks

that announce the time, and a connection with the telephone so communications

could be recorded.

Disc

Phonograph - History

Cylinders

peaked in popularity around 1905. After this, discs and disc players, most

notably the Victrolas, began to dominate the market. Columbia Records, and Edison competitor, had stopped marketing cylinders in

1912. The Edison Company had been fully devoted to cylinder phonographs, but,

concerned with discs' rising popularity, Edison

associates began developing their own disc player and discs in secret. Dr.

Jonas Aylsworth, chief chemist for Edison, and

later after his retirement in 1903, a consultant for the company, took charge

of developing a plastic material for the discs. The aim was to produce a

superior-sounding disc that would outperform the rivals' shellac records, which

were prone to wear and warping. Another difference from competitors' discs was

that the vertical-cut method was to be used for the grooves. In this manner,

the stylus would bob up and down in the groove, rather than from side to side

or laterally. Ten-inch records would run for 5 minutes per side at

approximately 80 r.p.m.

Although

Edison associates initially worked on the project in secret, when Edison discovered it, he took control of this new project

and gave it much of his personal attention.

Aylsworth

molded phenol and formaldehyde mixed with wood-flour and a solvent into a

heat-resistant disc. This material always remained absolutely plane, which was

essential as it formed the core of the disc record. A phenolic resin varnish

called Condensite was applied to the core, and then the disc was stamped in the

record press. The finished 10' disc weighed ten ounces, heavier than most,

partially due to the 1/4' thickness of the record. A diamond point was

obtained for the stylus. The Disc Phonograph and the Edison Discs were designed

to be an entire system, incompatible with other discs or disc players.

The

new Edison Disc Phonograph was shown for the first time publicly at the Fifth

Annual Convention for the National Association of Talking Machine Jobbers at Milwaukee, Wisconsin,

on July 10-13th, 1911. Press reported that the new machine was based on Edison's British 1878 patent in order to deter claims of

copyright infringement with Victor or Berliner. The new machine was also

mentioned in the Edison Phonograph Monthly in July of 1911, but it was over a

year before disc players or discs would be offered for sale.

By

the end of 1912, three basic models of the Edison Disc Phonograph had been

designed, ranging in price from $150 to $250, and the company salesmen took

them around the country. Soon after, the choice of models was extended to

feature less expensive players and luxury machines in stylish wood cabinets.

Prices for the discs started from $1.15 to $4.25, but later came down to $1.35

to $2.25. The discs were expensive to make because of the complicated chemical

processes used for them.

Initial

public reaction was not encouraging for several reasons. The Edison cabinets

were deemed to be less attractive than the Victrolas, and customers were

required to buy Edison discs only for Edison

players, since they were not compatible with other players. The laminated

surface of the discs also had a tendency to detach from the core material, and

surface noise was frequently apparent, which contradicted the aim of perfection

that the company was trying to achieve with its recordings. Still, the

phonographs and discs were touted as being acoustically better than those of

the competitors. In order to bolster claims of superiority, Edison

claimed that his records could be played 1,000 times without wear

Recitals

were also conducted to prove the merit of the discs. Edison

recording artists would sing along with a disc recording of their voices,

daring the audience to be able to tell the difference. In late 1915, Edison began its famous Tone Tests, which featured

artists alternating their live performance on a darkened stage with that on the

disc in front of large audiences, challenging them to detect a difference.

Reaction was positive to these tests, and reinforced the Edison

motto that the discs were 're-creations' of performances, not merely

recordings of them.

Additional

advertising for the Diamond Disc was secured through promotion of the Edison film The Voice of the Violin, made in 1915, which

featured a Tone Test by Anna Case. (The Library of Congress copy is incomplete

and, unfortunately, is lacking Case's performance.)

On

the disc label, sides were indicated by 'L' and 'R',

referring to the left side or the right side when stored vertically. The early

disc issues contained the Edison trademark, Edison's image, the title of the

selection, and the composer, all pressed into the glossy black surface of the

disc using a half-tone electrotype. The early issues did not carry the artists'

names, reflecting Edison's policy of not

seeking out name acts, but supposedly relying on the quality of the music

alone. In 1915, the artists' names began to be added to the labels. In 1921,

black paper labels with white Roman type began to be used, and were changed at

the end of 1923 to white labels.

By

1916, demand increased for console cabinets to house the disc players. The

Edison Company produced a series of period models to compete with those of the

Victor Company. The designer for the cabinets was H.D. Newson from the W.A.

French Furniture Company of Minneapolis.

Named 'The Art Models,' these cabinets came in English, French, and

Italian period styles, as well as Gothic styles. Prices ranged from $1,000 to

$6,000. Advertising for these models made it clear that the players themselves

were the same as lower-priced models; the inflated cost was for the cabinet.

In

1917 when the U.S.

became involved in World War I, the Edison Company created the Army and Navy

Model in answer to a request for machines from the United States Army

Depot

Quartermaster in New York.

The simple, basic machine sold for $60. The Department of War never purchased

any, but individual units bought them, some taking them overseas. The Army and

Navy Model was discontinued after the war's end.

By

1917, the Disc Phonograph had garnered considerable success in the marketplace.

This good fortune continued for almost seven years. In contrast, the cylinder

phonograph business declined; by 1925, the remaining cylinder customers had to

order directly from the factory. By 1920, Edison

was the only disc company not using steel needles or the lateral method of

grooves.

By

1924, business began to sour with the advent of competition from radio.

Operations were cut back, and experimentation began with long-playing records.

These were introduced in October 1926 along with four new console disc

phonographs. As a concession to the marketplace, attachments were also offered

so that the Edison phonographs could play the

laterally-cut records of competitors.

By

the latter half of the 20's, the company started to diversify its interests in

an attempt to stay viable. Thoughts of moving pictures with sound led the

company to develop an Ediscope which featured still pictures with narration.

This was envisioned as being appropriate for the children's market, since it

could be used for fairy tales and educational nature talks. Work was also begun

on the Cine-Music Phonograph, which was conceived to supply musical

accompaniment to motion pictures.

Edison

entered into the radio business in 1928 by taking over the Aplitdorf-Bethlehem

Electrical Company of Newark,

a move which allowed him to produce radio-phonographs. The Edison Company

further expanded into the field of radio by making programs for radio on

long-playing discs. Radio station WAAM of Newark, NJ, agreed to use the new

Rayediphonic Reproducing Machine and Radiosonic records in 1929, with the first

Radiosonic broadcast being aired on April 4. It appeared that the company had

finally found a profitable outlet.

In

the summer of 1929, the Edison company gave

into the popular trend and introduced the Edison Portable Disc Phonograph with

New Edison Needle Records, offering both the Diamond Discs and the new needle

records simultaneously.

These

changes did not measurably improve business, and on October 21, orders were

given to close the Edison disc business, with

the company stating that it would focus on the manufacture of its

radio-phonographs in the future.

Kinetophones - History

From

the inception of motion pictures, various inventors attempted to unite sight

and sound through 'talking' motion pictures. The Edison Company is

known to have experimented with this as early as the fall of 1894 under the

supervision of W. K. L. Dickson with a film known today as Dickson Experimental

Sound Film. The film shows a man, who may possibly be Dickson, playing violin

before a phonograph horn as two men dance.

By

the spring of 1895, Edison was offering

Kinetophones--Kinetoscopes with phonographs inside their cabinets. The viewer

would look into the peep-holes of the Kinetoscope to watch the motion picture

while listening to the accompanying phonograph through two rubber ear tubes

connected to the machine (the kinetophone). The picture and sound were made

somewhat synchronous by connecting the two with a belt. Although the initial

novelty of the machine drew attention, the decline of the Kinetoscope business

and Dickson's departure from Edison ended any

further work on the Kinetophone for 18 years.

In

1913, a different version of the Kinetophone was introduced to the public. This

time, the sound was made to synchronize with a motion picture projected onto a

screen. A celluloid cylinder record measuring 5 1/2' in diameter was used

for the phonograph. Synchronization was achieved by connecting the projector at

one end of the theater and the phonograph at the other end with a long pulley.

Nineteen

talking pictures were produced in 1913 by Edison,

but by 1915 he had abandoned sound motion pictures. There were several reasons

for this. First, union rules stipulated that local union projectionists had to

operate the Kinetophones, even though they hadn't been trained properly in its

use. This led to many instances where synchronization was not achieved, causing

audience dissatisfaction. The method of synchronization used was still less

than perfect, and breaks in the film would cause the motion picture to get out

of step with the phonograph record. The dissolution of the Motion Picture

Patents Corp. in 1915 may also have contributed to Edison's

departure from sound films, since this act deprived him of patent protection

for his motion picture inventions.

Electricity and Lightbulb -

History

Thomas Edison's greatest challenge

was the development of a practical incandescent, electric light. Contrary to

popular belief, he didn't 'invent' the lightbulb, but rather he

improved upon a 50-year-old idea. In 1879, using lower current electricity, a

small carbonized filament, and an improved vacuum inside the globe, he was able

to produce a reliable, long-lasting source of light. The idea of electric

lighting was not new, and a number of people had worked on, and even developed

forms of electric lighting. But up to that time, nothing had been developed

that was remotely practical for home use. Edison's

eventual achievement was inventing not just an incandescent electric light, but

also an electric lighting system that contained all the elements necessary to

make the incandescent light practical, safe, and economical. After one and a

half years of work, success was achieved when an incandescent lamp with a

filament of carbonized sewing thread burned for thirteen and a half hours.

Thomas Edison's greatest challenge

was the development of a practical incandescent, electric light. Contrary to

popular belief, he didn't 'invent' the lightbulb, but rather he

improved upon a 50-year-old idea. In 1879, using lower current electricity, a

small carbonized filament, and an improved vacuum inside the globe, he was able

to produce a reliable, long-lasting source of light. The idea of electric

lighting was not new, and a number of people had worked on, and even developed

forms of electric lighting. But up to that time, nothing had been developed

that was remotely practical for home use. Edison's

eventual achievement was inventing not just an incandescent electric light, but

also an electric lighting system that contained all the elements necessary to

make the incandescent light practical, safe, and economical. After one and a

half years of work, success was achieved when an incandescent lamp with a

filament of carbonized sewing thread burned for thirteen and a half hours.

There

are a couple of other interesting things about the invention of the light bulb:

While most of the attention was on the discovery of the right kind of filament

that would work, Edison actually had to invent a total of seven system elements

that were critical to the practical application of electric lights as an

alternative to the gas lights that were prevalent in that day.

These

were the development of:

- the parallel circuit,

- a durable light bulb,

- an improved dynamo,

- the underground conductor network,

- the devices for maintaining constant voltage,

- safety fuses and insulating materials, and

- light sockets with on-off switches.

Before

Edison could make his millions, every one of

these elements had to be invented and then, through careful trial and error,

developed into practical, reproducible components. The first public demonstration

of the Thomas Edison's incandescent lighting system was in December 1879, when

the Menlo Park

laboratory complex was electrically lighted. Edison

spent the next several years creating the electric industry.

The

modern electric utility industry began in the 1880s. It evolved from gas and

electric carbon-arc commercial and street lighting systems. On September 4,

1882, the first commercial power station, located on Pearl Street in lower Manhattan, went into operation providing

light and electricity power to customers in a one square mile area; the

electric age had begun. Thomas Edison's Pearl Street electricity generating

station introduced four key elements of a modern electric utility system. It

featured reliable central generation, efficient distribution, a successful end

use (in 1882, the light bulb), and a competitive price. A model of efficiency

for its time, Pearl Street

used one-third the fuel of its predecessors, burning about 10 pounds of coal

per kilowatt hour, a 'heat rate' equivalent of about 138,000 Btu per

kilowatt hour. Initially the Pearl

Street utility served 59 customers for about 24

cents per kilowatt hour. In the late 1880s, power demand for electric motors

brought the industry from mainly nighttime lighting to 24-hour service and

dramatically raised electricity demand for transportation and industry needs.

By the end of the 1880s, small central stations dotted many U.S. cities;

each was limited to a few blocks area because of transmission inefficiencies of

direct current (dc).

The

success of his electric light brought Thomas Edison to new heights of fame and

wealth, as electricity spread around the world. His various electric companies

continued to grow until in 1889 they were brought together to form Edison

General Electric. Despite the use of Edison in

the company title however, he never controlled this company. The tremendous

amount of capital needed to develop the incandescent lighting industry had

necessitated the involvement of investment bankers such as J.P. Morgan. When

Edison General Electric merged with its leading competitor Thompson-Houston in

1892, Edison was dropped from the name, and

the company became simply General Electric.

Edison Motion Pictures - History

Thomas

Edison's interest in motion pictures began before 1888, however, the visit of

Eadweard Muybridge to his laboratory in West Orange

in February of that year certainly stimulated his resolve to invent a camera

for motion pictures. Muybridge proposed that they collaborate and combine the

Zoopraxiscope with the Edison phonograph.

Although apparently intrigued, Edison decided

not to participate in such a partnership, perhaps realizing that the

Zoopraxiscope was not a very practical or efficient way of recording motion. In

an attempt to protect his future, he filed a caveat with the Patents Office on

October 17, 1888, describing his ideas for a device which would 'do for

the eye what the phonograph does for the ear' -- record and reproduce

objects in motion. He called it a 'Kinetoscope,' using the Greek

words 'kineto' meaning 'movement' and 'scopos'

meaning 'to watch.'

One

of Edison's first motion picture and the first

motion picture ever copyrighted showed his employee Fred Ott pretending to

sneeze. One problem was that a good film for motion pictures was not available.

In 1893, Eastman Kodak began supplying motion picture film stock, making it

possible for Edison to step up the production

of new motion pictures. He built a motion picture production studio in New Jersey. The studio

had a roof that could be opened to let in daylight, and the entire building was

constructed so that it could be moved to stay in line with the sun.

C.

Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat invented a film projector called the Vitascope

and asked Edison to supply the films and manufacture the projector under his

name. Eventually, the Edison Company developed its own projector, known as the

Projectoscope, and stopped marketing the Vitascope. The first motion pictures

shown in a 'movie theater' in America

were presented to audiences on April 23, 1896, in New York City.

The Failed Inventions

Thomas Alva Edison held 1,093 patents for

different inventions. Many of them, like the lightbulb, the phonograph, and the

motion picture camera, were brilliant creations that have a huge influence on

our everyday life. However, not everything he created was a success; he also

had a few failures.

One

concept that never took off was Edison's

interest in using cement to build things. He formed the Edison Portland Cement

Co. in 1899, and made everything from cabinets (for phonographs) to pianos and

houses. Unfortunately, at the time, concrete was too expensive and the idea was

never accepted. Cement wasn't a total failure, though. His company was hired to

build Yankee Stadium in the Bronx.

From the beginning of the creation of motion

pictures, many people tried to combine film and sound to make

'talking' motion pictures. Here you can see to the left an example of

an early film attempting to combine sound with pictures made by Edison's assistant, W.K.L. Dickson. By 1895, Edison had created the Kinetophone--a Kinetoscope

(peep-hole motion picture viewer) with a phonograph that played inside the

cabinet. Sound could be heard through two ear tubes while the viewer watched

the images. This creation never really took off, and by 1915 Edison

abandoned the idea of sound motion pictures.

From the beginning of the creation of motion

pictures, many people tried to combine film and sound to make

'talking' motion pictures. Here you can see to the left an example of

an early film attempting to combine sound with pictures made by Edison's assistant, W.K.L. Dickson. By 1895, Edison had created the Kinetophone--a Kinetoscope

(peep-hole motion picture viewer) with a phonograph that played inside the

cabinet. Sound could be heard through two ear tubes while the viewer watched

the images. This creation never really took off, and by 1915 Edison

abandoned the idea of sound motion pictures.

The

greatest failure of Thomas Edison's career was his inability to create a

practical way to mine iron ore. He worked on mining methods through the late

1880s and early 1890s to supply the Pennsylvania

steel mills' demand for iron ore. In order to finance this work, he sold all

his stock in General Electric, but was never able to create a separator that

could extract iron from unusable, low-grade ores. Eventually, Edison gave up on

the idea, but by then he had lost all the money he'd invested.

The

greatest failure of Thomas Edison's career was his inability to create a

practical way to mine iron ore. He worked on mining methods through the late

1880s and early 1890s to supply the Pennsylvania

steel mills' demand for iron ore. In order to finance this work, he sold all

his stock in General Electric, but was never able to create a separator that

could extract iron from unusable, low-grade ores. Eventually, Edison gave up on

the idea, but by then he had lost all the money he'd invested.

Conclusion

Thomas Alva Edison

was a man who influenced America

more than anyone else. He became throw his inventions one of the most important

figures that world knew. His name is immortal threw ages just because his

brilliant mind .

He was lucky

because he was a businessman too, and he could start the production of all his

invention which help us nowadays. Beside all this he ruined the hopes of others

peoples to try to assume the same inventions , as we can say now he registered

these devices with the original brand no copyright allowed.

In

my opinion, Thomas Edison was a person who deserves our respect for his

influence on political thought and for the long-lasting effects of all that he

accomplished during his long and fruitful career.

Bibliography

Books

(information)

1. Edison:

The man who made the future by

Ronald W. Clark

2. Edison:

Inventing the Century by Neil Baldwin

3. Edison

by Matthew Josephson. McGraw Hill

and brought

and brought  The success of his electric light

brought

The success of his electric light

brought  The Inventions of Thomas Edison

The Inventions of Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison's greatest challenge

was the development of a practical incandescent, electric light. Contrary to

popular belief, he didn't 'invent' the lightbulb, but rather he

improved upon a 50-year-old idea. In 1879, using lower current electricity, a

small carbonized filament, and an improved vacuum inside the globe, he was able

to produce a reliable, long-lasting source of light. The idea of electric

lighting was not new, and a number of people had worked on, and even developed

forms of electric lighting. But up to that time, nothing had been developed

that was remotely practical for home use.

Thomas Edison's greatest challenge

was the development of a practical incandescent, electric light. Contrary to

popular belief, he didn't 'invent' the lightbulb, but rather he

improved upon a 50-year-old idea. In 1879, using lower current electricity, a

small carbonized filament, and an improved vacuum inside the globe, he was able

to produce a reliable, long-lasting source of light. The idea of electric

lighting was not new, and a number of people had worked on, and even developed

forms of electric lighting. But up to that time, nothing had been developed

that was remotely practical for home use.

From the beginning of the creation of motion

pictures, many people tried to combine film and sound to make

'talking' motion pictures. Here you can see to the left an example of

an early film attempting to combine sound with pictures made by

From the beginning of the creation of motion

pictures, many people tried to combine film and sound to make

'talking' motion pictures. Here you can see to the left an example of

an early film attempting to combine sound with pictures made by  The

greatest failure of Thomas Edison's career was his inability to create a

practical way to mine iron ore. He worked on mining methods through the late

1880s and early 1890s to supply the

The

greatest failure of Thomas Edison's career was his inability to create a

practical way to mine iron ore. He worked on mining methods through the late

1880s and early 1890s to supply the

![]()